Sovereign Device Security: What the BitLocker Case Reveals About Cloud-Controlled Infrastructure

Why This Story Matters for Sovereignty

Digital assets don’t float in the abstract. They live on devices, inside systems, and behind layers of infrastructure that quietly determine who holds real control. That’s why the Microsoft–FBI BitLocker case isn’t just a headline — it’s a sovereignty lesson.

Most people assume encryption equals protection.

But encryption only protects you when you hold the keys. The moment a platform stores those keys “for convenience,” your autonomy becomes conditional.

This case exposes the core tension of the digital era:

Encryption is not sovereignty. Control of the keys is sovereignty.

When Microsoft can hand over BitLocker recovery keys because they were silently uploaded to the cloud, it reveals a truth most users never confront. The systems we rely on are designed for access, not independence.

And if someone else can unlock your device, the question becomes unavoidable:

Do you truly own anything stored on it?

What Happened Between Microsoft, the FBI, and BitLocker

The BitLocker case began during a federal investigation in Guam, where agents seized three laptops protected by Microsoft’s built‑in encryption. Under normal conditions, encrypted devices should remain locked unless the owner provides the key.

"But BitLocker includes a silent default: when a user signs into Windows with a Microsoft account, the recovery key is automatically uploaded to Microsoft’s cloud."

So when investigators obtained the proper legal orders, Microsoft simply provided the recovery keys stored in the suspects’ accounts. The FBI didn’t break encryption. They didn’t bypass security. They accessed the data because the company—not the user—held the keys.

This is the sovereignty lesson: encryption is meaningless when someone else controls the recovery path. The system worked exactly as designed, and that design placed the user’s protection behind a corporate gate.

The real question this case exposes is larger than BitLocker:

How do you store digital property in a way that cannot be unlocked by a platform, a breach, or a subpoena?

How BitLocker Stores Your Keys Without You Realizing

Modern Windows devices enable BitLocker automatically and then quietly upload the recovery key to the user’s Microsoft account. No warning. No explicit consent. No moment where the user chooses sovereignty over convenience.

The system assumes you want recoverability, not autonomy.

This creates a dependency most people never see: your encryption is only as private as Microsoft’s cloud. If the company is breached, compelled, or compromised, your device is effectively unlocked.

This is the broader pattern of modern computing.

Cloud convenience is marketed as safety, but it often becomes the very mechanism that undermines sovereignty. Your device feels personal, but the infrastructure around it is designed for access—corporate access, legal access, and sometimes unauthorized access.

The uncomfortable truth is simple:

Your computer and your cloud accounts hold more secrets than you realize—including the keys to your own encryption.

Who Holds the Keys Controls the Asset

The BitLocker case crystallizes a principle that governs every digital asset: the entity that holds the keys controls the asset. Encryption only works as a shield when the keys remain in your custody. If a company can unlock your device, your protection depends on its policies, security posture, and legal obligations — not on your sovereignty.

There are only two forms of encryption:

- Encryption you control — keys stored offline, never synced, never shared

- Encryption someone else can unlock — keys stored in a cloud, accessible to a platform, breach, or subpoena

Centralized key storage creates a single point of failure. A breach of the platform becomes a breach of you. A legal request to the company becomes access to your device. The math behind encryption remains strong, but the sovereignty collapses because the recovery path lives outside your hands.

Cloud‑stored keys don’t weaken encryption — they weaken ownership. And the moment you outsource the keys, you outsource control.

What Experts Warn About Cloud‑Stored Keys

Cryptographers like Matthew Green have long warned that centralized key storage turns strong encryption into a weak security posture. When millions of recovery keys sit inside a single corporate cloud, the threat model shifts dramatically.

If Microsoft is breached, your encryption is breached.

If Microsoft is compelled, your encryption is compelled.

This isn’t hypothetical. Microsoft has faced multiple high‑profile intrusions, including nation‑state attacks that exposed internal systems. Each incident reinforces the same principle: centralization concentrates risk.

Cloud‑stored keys don’t weaken the math behind encryption—they weaken the sovereignty behind it. The protection depends on a corporation’s policies, security practices, and legal obligations, not on your custody.

The doctrine is clear:

Every third party you trust becomes an attack surface.

How This Case Exposes a Blind Spot in Your Digital Infrastructure

For anyone building a livelihood through digital assets, this case cuts deeper than a headline. It reveals how much of your intellectual property, creative output, and operational systems depend on devices and cloud accounts you did not design and do not control. Drafts, frameworks, client work, automations, resale workflows, and proprietary knowledge all live on machines that quietly sync themselves to corporate ecosystems.

What feels like a personal workspace is, in reality, a terminal inside someone else’s architecture.

Cloud services have trained an entire generation of digital workers to equate convenience with safety.

Syncing feels responsible.

Backups feel protective.

Defaults feel harmless.

But the BitLocker case exposes the truth beneath that comfort: the cloud doesn’t just store your files — it stores the keys to your files. And when those keys sit inside a corporate environment, your sovereignty becomes conditional.

This is the blind spot that defines the modern digital landscape. Most people never question who holds the keys to their devices, their data, or their livelihood. They assume encryption equals control. They assume privacy is a setting. They assume autonomy is the default.

It isn’t.

The BitLocker case forces a new understanding: sovereignty is not a belief or a mindset.

It is a configuration.

A system.

A deliberate set of choices about where your assets live and who can unlock them.

This moment reveals the infrastructure beneath your digital life — and the stakes of ignoring it.

How to Take Control of Your Encryption Keys

Sovereignty begins with custody. BitLocker can operate as a sovereign tool, but only when you override the defaults that place your recovery keys inside Microsoft’s cloud.

1. Check Whether Your Keys Are Stored Online

Visit your Microsoft account’s device page and look for BitLocker recovery keys. If they appear, they are stored in the cloud and accessible to Microsoft.

2. Remove Cloud‑Stored Keys

Delete the keys from your Microsoft account. BitLocker remains active — you simply reclaim custody.

3. Store Keys Offline

Use physical storage:

- Printed copy

- Offline USB drive

- Fireproof safe

- Avoid cloud drives, screenshots, email, or synced password managers.

4. Configure Your Device for Sovereign Operation

- Use a local account, not a Microsoft login

- Disable automatic syncing

- Turn off cloud‑based recovery features

- Ensure BitLocker is enabled with user‑held keys only

Sovereign Defaults Checklist

- ☐ Keys stored offline

- ☐ Local account only

- ☐ No cloud backups of recovery keys

- ☐ No automatic syncing

- ☐ Physical custody of key storage

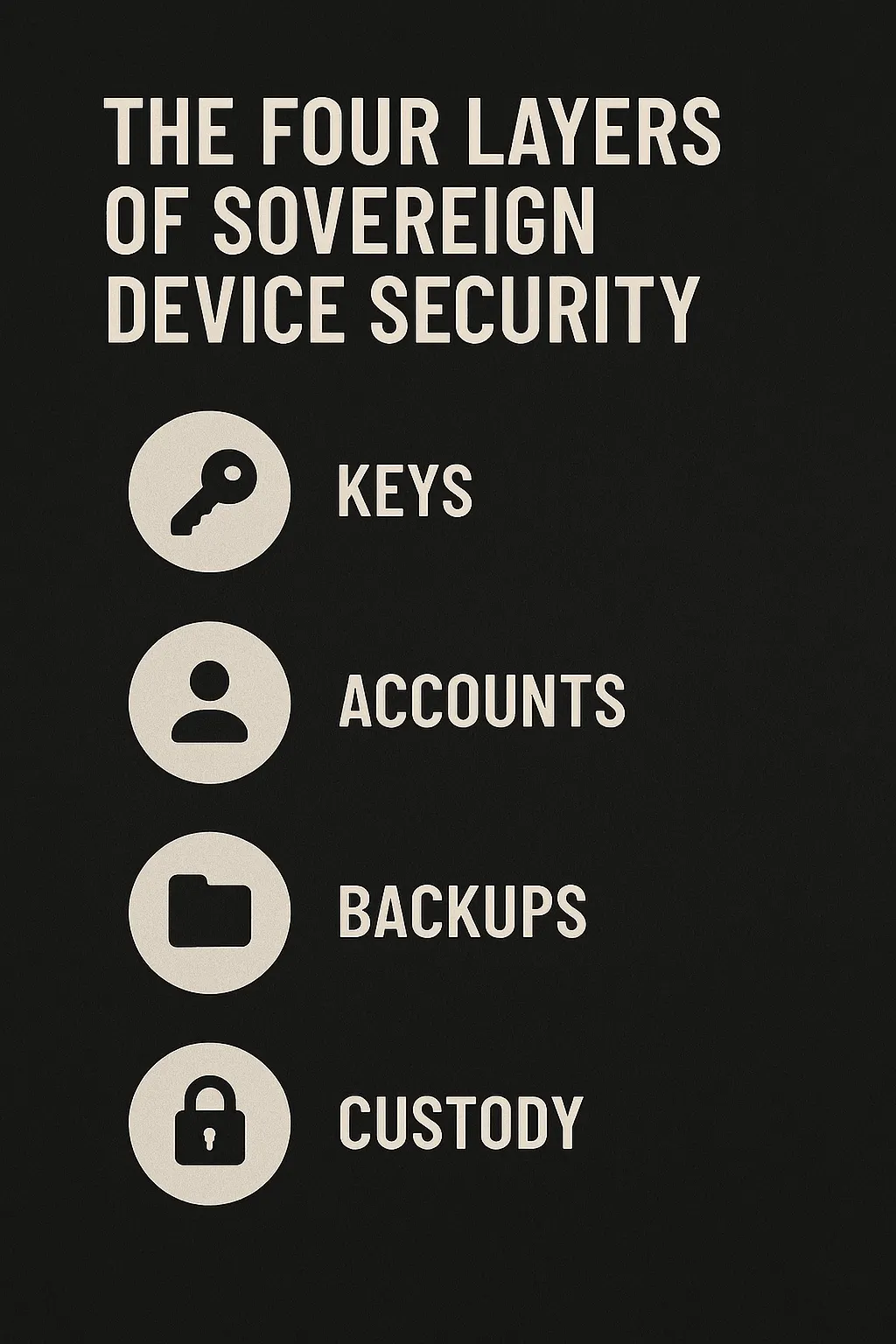

The Four Layers of Sovereign Device Security

Sovereign operators evaluate every device through four layers of control. These layers determine whether a machine is truly yours or simply leased through a platform’s architecture.

- Keys - The first layer is custody.If the keys live anywhere but in your hands, the device is not sovereign. Control begins with possession.

- Accounts - Cloud‑linked identities create recovery paths you do not govern. Local accounts eliminate external access and collapse the platform’s leverage.

- Backups - Backups are either sovereign or syndicated. Offline copies preserve autonomy. Synced copies replicate your vulnerabilities across systems you don’t control.

- Custody - Sovereignty requires physical control. A device you cannot physically secure is a device you cannot fully protect.

Cloud Convenience Is an Attack Surface

The BitLocker case is not an isolated flaw — it’s a symptom of a much larger pattern shaping the modern digital world. Across every major platform, convenience is engineered as the default, and sovereignty becomes the tradeoff hidden beneath it.

Cloud syncing, automatic backups, cross‑device continuity, and seamless account recovery all appear to make life easier. But each one introduces a new dependency, a new point of access, and a new place where your keys — literal or metaphorical — can be stored, copied, or compelled.

This pattern repeats everywhere:

- Apple stores iCloud backups that can unlock your device history.

- Google syncs passwords, settings, and authentication tokens.

- Password managers replicate vaults across servers.

- Messaging apps keep “encrypted” conversations recoverable through cloud‑linked keys.

The architecture is consistent: centralize the keys to simplify the experience. But centralization always creates an attack surface. A breach of the platform becomes a breach of you. A subpoena to the company becomes a subpoena to your life. A policy change becomes a shift in your threat model.

The BitLocker case simply makes the invisible visible. It shows how quickly encryption collapses when the keys live anywhere other than your hands. It shows how easily sovereignty evaporates when convenience becomes the default.

The doctrine is clear and non‑negotiable:

If you don’t control the keys, you don’t control the asset.

What This Case Signals About the Future of Digital Sovereignty

The BitLocker case is a preview of the world we’re moving into — a world where the tension between users, platforms, and governments will only intensify. As more of life becomes digital, the battle over who controls the keys to that life becomes unavoidable.

Platforms will continue to centralize access in the name of convenience. Governments will continue to expand their reach in the name of security.

And users will be caught in the middle unless they choose a different path.

Digital sovereignty will not be granted by the systems we use. It will be claimed by the individuals who understand how those systems work — and who configure their lives accordingly. That is the mission of Digital Asset Insider: to teach sovereignty as a skill, expose the hidden dependencies built into everyday technology, and equip readers with systems that create control rather than fear.

This case makes one truth impossible to ignore: the future belongs to those who hold their own keys.

Not metaphorically.

Literally.

The path forward is clear.

Audit your dependencies.

Reclaim your keys.

Build systems that cannot be unlocked by anyone but you. The era of blind trust in platforms is ending, and a new era of intentional, sovereign digital ownership is beginning.